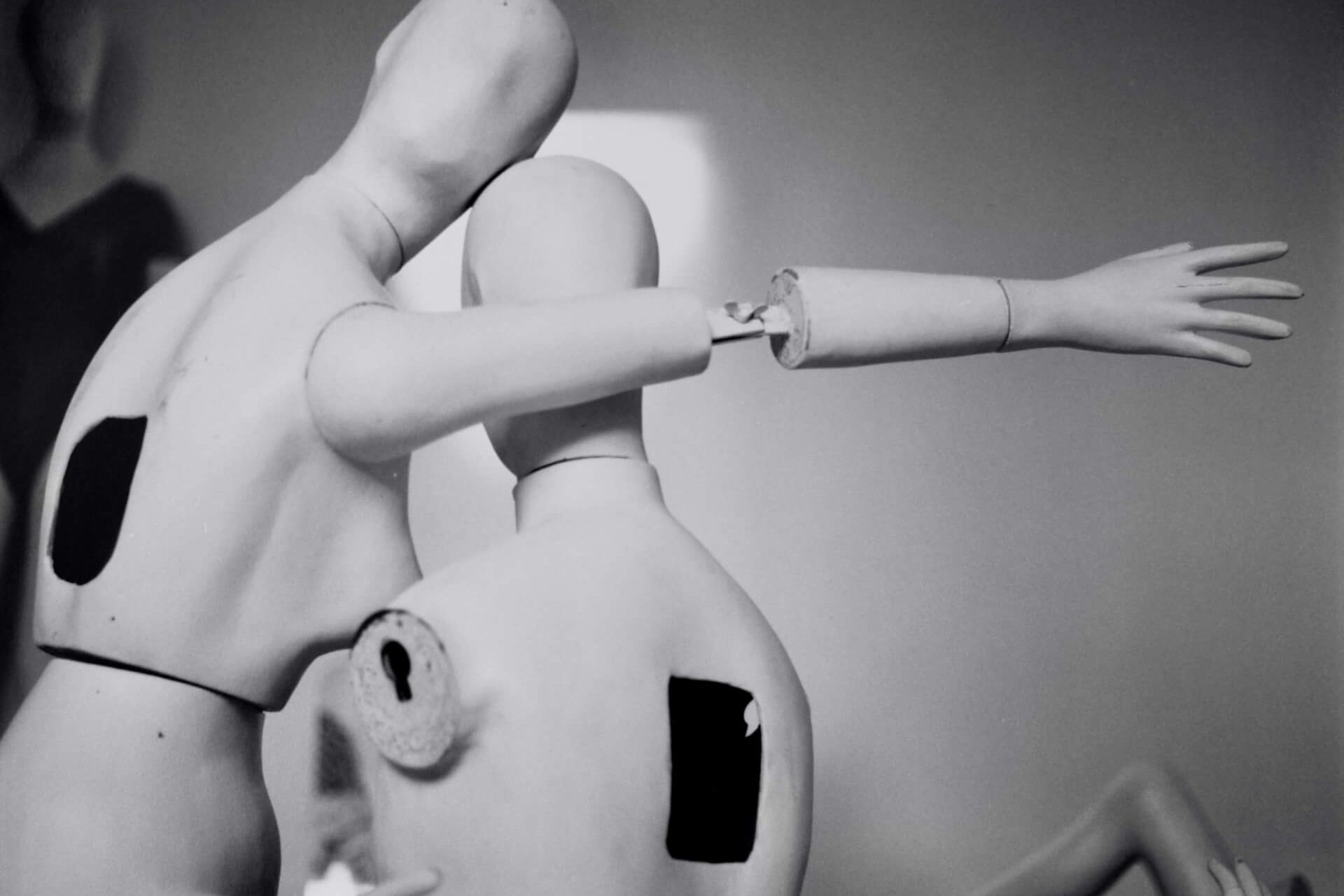

Give Me A Soul című fotósorozat a pécsi Zsdrál & Design Galériában

„A fotográfia feladata a dolgok valódi természetének, belsőjének és életének a megörökítése.” André Kertész Szabó Zsolt fotográfiai munkásságában…

Isparomar York (Szabó Zsolt): Take Me To Paradise

Fotósorozat a 2001. szeptember 11-i terrortámadás emlékére, 2018. szeptember Ahogyan elménk fényképezőgépe vakuként világítja meg a 2001-es new york-i…